Nearly ten years ago I was asked to be the guest speaker at an event at a college in Maryland. I posted my presentation on my old blog, which is now defunct, AND I changed computers enough times so that I didn’t have the file anymore. This morning I found my one and only paper version and immediately created a document on my current computer (which saves things to the cloud). Hopefully I won’t lose it again. Anyway, here is the speech I gave nearly a decade ago…

I’d like to begin by telling you a story about coming to the labyrinth. Sometime in 1993, I went to my friend, Linda’s house for a cup of tea and a visit. While I was there, she handed me a small, photocopied brochure with an image of a labyrinth on the front. Another friend, who I knew casually, had gone to an annual Unitarian General Assembly gathering a few weeks prior, and had brought the brochure to Linda, asking her to pass it along to me. This woman didn’t know quite why but felt strongly that I should have the brochure. So, that is the first time I remember seeing a labyrinth. And I fell in love. From that moment on, I have been building labyrinths and exploring different ways to experience them.

But it isn’t the first time I was in the presence of the labyrinth. Two years before, in 1991, I had gone to France & visited Chartres Cathedral. I had noticed an elaborate stone pattern in the floor, but it was covered with chairs, and I couldn’t tell quite what it was. I moved a few of the chairs, but not enough to uncover the labyrinth. And then in 1994, I read Jean Shinoda Bolen’s book, Crossing to Avalon, about her personal mid-life journey. She visited Chartres and did remove all the chairs on the labyrinth, walking it in deep prayer. Finally, I knew what the design in the stone floor had been! And sometimes that’s the way it happens with the labyrinth. A recognition, a calling from deep within.

By 1995, I had gathered a group of 20 or 25 people to paint a replica of the Chartres labyrinth on canvas. At that time, there were no kits, not even any templates. I went to northern Virginia to meet and consult with a few people who had made one and spoke by telephone with a man in the Midwest (who turned out to be Robert Ferre), and emailed with Jeff Saward, the editor of Caerdroia, a labyrinth journal published in England. I gathered measurements and advice. We ordered 100 yards of sail-weight canvas and paid a sail-maker to sew Velcro edges on six 42-foot lengths, each strip being 7 feet wide. And then we had a 42-foot square canvas to paint on!

Next, we built an enormous compass in the barn of one of the group members. The wooden compass arm was a 21-foot-long 4×4, and it perched on a wooden base pivot. We drilled 13 holes along the compass arm to hold pencils vertically, so that, with a crew of people working carefully together, we could slowly draw all of the concentric circles we needed at one time. It worked! From large pieces of corrugated paper, we made a precise template for drawing the turns, one for drawing the petals of the rose at the center, and another for drawing the lunations around the outer edge. Once all of the lines were penciled in, we carefully erased the unnecessary parts of lines from the original concentric circles and were ready to begin painting.

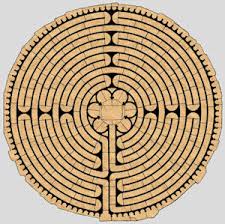

So, what is a labyrinth? A unicursal path, usually within a circle, but not always. There are a few squared labyrinths. It is one meandering path, moving in and out and back and forth, filling all of the available space until finally the center is reached. The same path is retraced to find the way out. The entrance and the exit are one. There are twists and turns in a labyrinth, but no wrong turns. No intersections. No dead ends. A labyrinth is not a puzzle or a game. It isn’t a matter of skill or chance. That is a maze. A labyrinth is something very different. A maze engages our left brain, our intellect, our rational mind. A labyrinth also engages our right brain, our creative and intuitive self. It draws us inward and offers us a metaphor for the spiritual journey of life. The labyrinth helps to balance the left and right sides of the brain, as we wend our way back and forth, in and out, back and forth. We connect to our more deeply creative selves, our intuition, our divinity.

Humans have been drawing and building labyrinths for 3500 to 4000 years. We find them etched in the stone of cave walls, scratched on clay tablets, imprinted on ancient coins and in petroglyphs. Always they seem to have a spiritual or sacred significance. Labyrinths are found all over the world, from India to Scandinavia, from Peru to Britain, from France and Spain to the American southwest. The wisdom of the labyrinth seems to arise in human consciousness in some spontaneous way, and then recede again. Sometimes we are called to it, or it is called to us, and sometimes we forget. It is the nature of life, the nature of the human experience.

Anne Morrow Lindburgh wrote about Ebb and Flow. She said:

“We have so little faith in the ebb and flow of life, of love, of relationships. We leap at the flow of the tide and resist in terror its ebb.”

The labyrinth offers us a kind of walking meditation, a metaphorical journey, during which our bodies can learn to experience these truths in a deep and sacred way. We encounter moments of autonomy, moments of coming together, moments of one-on-one relationship, and moments of moving away. In the labyrinth, we experience a journey of metaphor. The flow of life, and its ebb, is as fluid as the flow of water, always changing. We can feel in our bodies the joys of intimacy and of community, and we can feel the pain and anguish of loss.

The two most important Classical labyrinths are the older and less complex Cretan type with 7 circuits and the Chartres type with 11 circuits. The labyrinth that we are walking today is a replica of the Chartres labyrinth. The Chartres design seems to have been developed by a monk, drawing on the back of an illuminated manuscript he was working on, and is mathematically based upon the earlier 7 circuit design. It was installed as a stone design in the floor of Chartres Cathedral in the early 1200’s and was used as the last part of a pilgrimage that many early Christians took, when they were unable to travel to their holy land. Sometimes called the Rose Labyrinth because of the six-petaled “flower” at the center, this labyrinth sits in the shadow of the famous Rose Window at Chartres. In fact, it is positioned so that if the tower wall that holds the Rose Window could be hinged at the floor and laid down, the center of the rose window would precisely overlay the labyrinth. Sacred geometry in architecture.

And yet, the labyrinth doesn’t seem to require such astonishing mathematical precision. No matter how we draw one, it creates sacred space. The lines of a labyrinth can be pencil on paper scraps, cornmeal on a lawn, pebbles, large stones, tall plants. They can be drawn with lengths of looping rope, using a stick to form grooves in sand on the beach, or digging narrow trenches in turf. They are on jewelry, pottery, coins, and fabric. We find them carved into stone above church entrances and etched into prehistoric cave walls. They can be large enough to walk and small enough to carry in your pocket. Walking labyrinths are found in cathedrals and prisons, churches and parks, hospice centers, private gardens and college campuses. No matter where the labyrinth is, or how the lines are drawn, the lines are not the labyrinth. Let me say that again. No matter where the labyrinth is, or how the lines are drawn, the lines are not the labyrinth. The path is the labyrinth. The space we engage with is the labyrinth. After all, it isn’t the walls that turn a building into a sanctuary.

So, the labyrinth is based on principals of sacred geometry and architecture, even astronomy, and has been since its beginning. Before humans had developed a language to explain the geometry, they were still creating labyrinths that utilized the unexpressed concepts. Sacred geometry is based on patterns that occur in nature. Circles, spirals, meanders. The Golden Mean. The Fibonacci Sequence. The labyrinth is a physical representation of a deep wisdom that is held in what Carl Jung called “the collective consciousness”. Labyrinths have arisen spontaneously around the globe for thousands of years, and then receded again. No one knows why. The labyrinth is metaphor made manifest. And walking the labyrinth presents us with metaphors and insights into the Journey of Life.

Author, Oriah Mountaindreamer muses:

“What if… life is not a maze but a labyrinth, a path that meanders to give us different views, doubles back on itself to give us multiple chances to see clearly, lets us revisit our joys & sorrows but in the end always takes us to the sacred center – to Life, to Love, to the Wholeness of which we are made & by which we are held?”

So, how do you walk a labyrinth? There are as many ways as there are labyrinths, as many ways as there are walkers, as many ways as there are walks… Perhaps a walking meditation; heel rolling to toe and pause, heel rolling to toe and pause… Perhaps step, breathe, step. Perhaps a even prayerful dance. Early Christian pilgrims walked on their knees. You can take a question to the labyrinth, ask it, offer it and then open yourself to insights that occur. Looking for inner peace? The labyrinth is a perfect tool. Have a wedding in the labyrinth – perhaps one partner waiting for the other at the center.

Walking the labyrinth can be about the lesson of surrender. Surrender to the moment you are in. As Ram Das says, “Be here now.” Surrender to who we truly are. Surrender to the path. And then follow it. One step at a time.

When walking the labyrinth, there are no decisions to be made once you have made the decision to put your foot on the path. Again, from Oriah Mountaindreamer, “It’s not a problem to be solved, not a test to be passed, but a journey to savour and drop into with each step.”

How might you prepare to walk the labyrinth? Step up to the entrance. Pause. Breathe. Find your quiet center. Feel the earth beneath your feet and the sky in your lungs. Reach for the sun, the stars, the moon, and sense the balance in your earthly body. Walk from your center, perhaps peeling away layers of mask and costume, leaving them behind as you walk. Becoming more and more your authentic self as you walk. Pausing when feel it, moving forward when you feel it. Stepping into the labrys at the turns if they call to you. And then returning to the path. Arrive at the center as your true and open self. Wait there for as long as you will. And then rise, and follow the same path, winding your way back out.

I have another story to tell you. Years ago, a group of us had taken the canvas that we painted to Millersville University at the request of the interfaith chaplain and set it up in the student center for finals week. I had family visiting from England and Canada during the same week & wanted to share this interest of mine with them. I come from an interesting family. We are a diverse collection of intellectuals and mystics, healers and computer programmers. My aunt is a very rational, intellectual Oxford tutor of anthropology. As our family walked together in silence, she began to weep. She wept, and she cried. And then she rested in the center and emerged tender and open. Later, as we were walking out of the building, she asked me about it. She wanted a rational explanation. I told her many of the things I’ve told you, about metaphor and about encountering ourselves on our life’s journey. About the connection we can make to our deep selves, to the divine. And she said, “That’s impossible. That doesn’t make any sense.” I looked at her and replied, “You are the one who just had the intense experience.”

So, if you remember nothing else, remember this. There is no right way and no wrong way to interact with a labyrinth. There is only what your body and spirit call for. In this moment.

Please do not copy, share or reprint this without my written permission. You may contact me at [email protected]

Copyright 2013, Sarah C Preston

What a beautiful experience to share!